Know Your Eggshed!

I first heard of the term “eggshed” while chatting with Karl Hammer, owner of the Vermont Compost Company (VCC). We were standing on a hillside overlooking mountains of compost. These compost piles were made from food residues collected from about 49 institutions including the schools, restaurants, company cafeterias, and any other organization that produced enough food scraps to merit collecting. Vermont has a zero-waste policy so instead of calling food leftovers “waste”, they call the biomass “residuals”.

What is unique about the Vermont Compost Company is that they employ about 1,200 free range chickens to help create their organic compost. The chickens turn and aerate the fermenting piles, while keeping the insect and rodent populations down. The chickens glean food scraps off the road and other places to keep the operations tidy. They also grace the piles with their manure and feathers adding valuable nitrogen. The fermenting compost piles had no smells putrid of garbage like landfills do. They smelled mostly of dark chocolate colored, musky humus in the making.

The VCC's 1,200 chickens work every day — and not even for chicken feed! They get all their food completely off the compost piles. They estimate that the chickens combined efforts are worth about 4 tons of fuel-free, heavy equipment that work 365 days a year, rain, snow or shine.

Karl was explaining to me that his “clucking composters” would lay, on average, about 1,000 dozen eggs a month (12,000 organic eggs/year). Karl went on to explain that these eggs helped fulfill the Montpelier “egg shed”. The Vermont Compost Company's could not be better located for the local egg shed. Their address is 1996 Main Street, in Montpelier, the State capital of Vermont.

Karl was explaining to me that his “clucking composters” would lay, on average, about 1,000 dozen eggs a month (12,000 organic eggs/year). Karl went on to explain that these eggs helped fulfill the Montpelier “egg shed”. The Vermont Compost Company's could not be better located for the local egg shed. Their address is 1996 Main Street, in Montpelier, the State capital of Vermont.

Let’s look at the definition of watershed to give the egg shed concept more shape. A watershed is defined by the Environmental Protection Agency as: "The area of land where all of the water that is under it, or drains off of it, goes into the same place".

An eggshed can be defined as: The eggs produced within a certain distance that go to a specific place".

The concept of eggsheds become real once we know how the average number of eggs humans eat in a specific location, and how many hens are needed to produce those eggs. Let’s use the following definition;

"An egg shed is the number of eggs a group, or community, consumes that are produced within a specific distance, within a period of time—usually a year."

Here’s How to Calculate Your Egg Shed

Now that we've defined what an egg shed is, we can establish a formula to make it practical. The US Poultry and Egg Association estimates that the average per capita egg consumption in 2012 was 249 eggs/person. For our egg shed formula, let's round that average up to 250 eggs consumed/person.

American Egg Board estimates the average commercial laying hen produces about 265 eggs/year. Heritage laying hens lay fewer eggs from about 200 to 270 eggs depending on the breed. For our egg shed formula, we'll assume an average hen lays 250 eggs/year.

That works out nicely so that 1 laying hen will produce enough eggs for 1 person each year.

Now let’s calculate how many eggs your egg shed requires. Let's use a population of 30,000. How many eggs would a population of 30,000 consume each year? Here is the formula:

Egg shed requirement = (population)(250 eggs laid per hen per year )=total number of eggs needed/year.

Just plug in the numbers:

Egg shed = (30,000 population)( each person eating an average of 250 eggs/year) = 7,500,000 eggs.

Yolks! Seven and a half million eggs for 30,000 people! That seems like a lot to produce!

But let’s run the model again with different flock sizes.

What if just 10% of the population kept 10 hens in family flocks.

For our population of 30,000, 10% would be 3,000 family flocks.

Egg shed = (3,000 family flocks)(10 hens each flock) (producing 250 eggs/year) = 7,500,000 eggs. That meets the egg shed!

What if chickens are not legal in your community ? Then you could support local farmers.

If 1% of the population—300 farmers kept 100 hens each laying 250 eggs/year = 7,500,000 eggs & meets the egg shed.

If 5% of the population—150 farmers kept 200 hens each laying 250 eggs/year = 7,500,000 eggs & meets the egg shed.

If 2% of the population—60 farmers kept 500 hens each laying 250 eggs/year = 7,500,000 eggs & meets the egg shed.

Of course, in chicken-friendly, local food supportive, green low-carbon-footprint-transistion communities—there are backyard flocks and small family farms producing eggs. The take-away message is that eggsheds for a family, or a community is relatively east to meet.

What About Egg Production in Chickens That Are too Young or Older?

Hens in factory farms are kept in strictly controlled environments. The birds have constant access to feed, water, and are managed to control the birds replacement of feathers (molting). This makes the hens are in sync for the timing of egg production. They have a life span of about 2 years before being processed for stew meat. In backyard and truly free-ranging flocks on grass, hens will not produce eggs as consistently as commercial birds. Why? Some reasons are below.

• Some birds in the flock might be younger, and not mature enough to lay eggs yet. It takes 5 to 6 months for a chick to mature and begin laying eggs.

• As hens get older they don't lay as many eggs as in their first 2 years. Egg production drops about 10% per year. An older hen still lays a significant number of eggs, but not as many as younger hens. The older hen's eggs tend to be large, but fewer.

• Some hens will be in molt — growing new feathers. Molting can happen at different times of the year but it is usually in the fall. While molting, egg laying decreases, and often stops until the new feathers grow in. If you were a chicken, which is more important, using your body's protein and energy growing a new suit feathers, or produce eggs?

• Many family flocks and small family farmers will have heritage and duel-purpose chickens (produce both meat and eggs). The egg production in these flocks will be lower.

• Many small private flocks will have roosters to help with predator protection. Roosters don't contribute to egg production, but they have other charms and talents helpful to flocks.

• When a hen goes broody and wants to sit on eggs her egg laying ceases. Incubating eggs until they hatch takes 3 weeks. And a hen mothering the chicks until they are old enough to fend for themselves takes another 5 to 7 weeks. This puts a laying hen out of egg production for a total of about 2.5 months.

• Extremes in temperatures (severe heat or cold) can cause a hen to slow, or cease laying.

• Consistent access to quality feed that contains enough protein affects egg laying. As does access to fresh water.

• Changes in daylight affect egg laying. As the days get shorter — egg laying slows and often stops. Then, as days get longer, a hen's egg laying increases. That's Nature's way. In winter, when the days are shorter and temperatures drop toward freezing, it is a hard time for a hen to incubate eggs, keep the chicks warm and find enough food for the babies to eat. Spring is the natural time for a hen to increase egg laying for producing chicks.

With all these egg production variables in the free-range and family flocks how can you estimate the number of hens needed for your egg shed? The number of hens will be different to meet the eggshed quota.

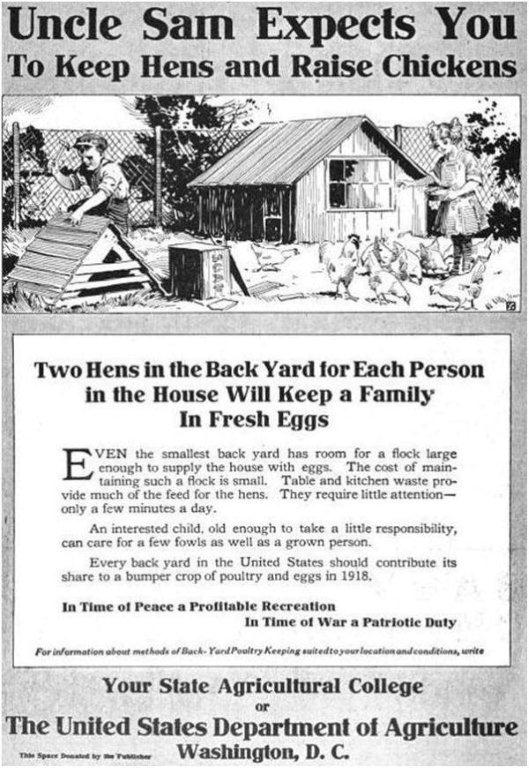

Below is a USDA poster from 1981 with the formula for a family egg shed. The USDA states that:

" 2 hens per every member in the household

will keep a family in fresh eggs." —USDA Poster, 1918

Why 2 hens instead of the 1 hen-per-capita we used in our egg shed formula? Because, not all hens in family flock and free-range flocks will laying consistently throughout the year for the reasons listed above. Weather, feed, exercise, brooding, molting, environment all affect egg laying.

So having 2 hens for every house hold member allows for the young chicks to mature, and the older hens to decrease or stop laying for a variety of reasons. This poster goes on to state:

"Uncle Sam Expects YOU to Keep Hens and Raise Chickens".

Notice that Uncle Sam didn't just suggest, or imply it was a good idea. No! He "EXPECTS" you to do your duty and keep a family flock. Be a responsible citizen and keep chickens. Our benevolent Uncle Sam continues to declare that:

"Even the smallest back yard has room for a flock large enough to supply the house with eggs.  The cost of maintaining such a flock is small. Table and kitchen waste provide much of the feed for the hens. The require little attention—only a few minutes a day. An interested child, old enough to take a little responsibility, can are for a few fowls as well as a grown person. Every back yard in he United States should contribute its share to a bumper crops of poultry and eggs in 1918.

The cost of maintaining such a flock is small. Table and kitchen waste provide much of the feed for the hens. The require little attention—only a few minutes a day. An interested child, old enough to take a little responsibility, can are for a few fowls as well as a grown person. Every back yard in he United States should contribute its share to a bumper crops of poultry and eggs in 1918.

In peace a profitable recreation. In war a patriotic duty". —US Department of Agriculture or Your State Agricultural College, 1918.

Egg Miles in Your Egg Shed

Another useful indicator in determining your egg shed is the distance an egg has to travel from production to your table. This is important because of the associated energy requirements for refrigeration and transport.

The egg mile(s) from family flocks or local farms is easy to calculate. Just measure the distance from your coop — usually in yards (excuse the pun) to your kitchen. Or estimate the distance from your local producer whose address will be on a table on the egg carton.

To calculate the egg miles for factory eggs, get the address off the egg carton. Somewhere the producer's address, or the location of the distribution/packing facility will be printed on the carton.

On some cartons, there won't be an address, but there will be a phone number you can call. When you call, you will eventually get someone who will ask for a number that is printed on the carton along, with the expiration date. With that, they can tell you where the eggs were produced, packaged and/or distributed. With the egg-source location, go to Google Maps, or your GPS and plug in the information and directions from there to your home or grocery market. That will tell you the egg shed miles from factory or packing plant to your table.

In summary, the locavore movement and local foods are taking center stage on many folks tables. Many, people migrate to local foods because of health problems. Food sheds are becoming frequent topic of conversations not just with us hippie-foodsters, but also at colleges, green festivals, blogs, websites and even discussed in many city council meetings. There is a Foodshed Magazine dedicated to educating the public and promoting local producers.

The bottom line is — with family flocks, and by supporting local family egg producers — is is possible for a community to be self-sufficient in egg production; one of the most easily digestible and highest quality forms of protein on the planet.

This is yet another reason to change the local laws to encourage family flocks and support local family farms.

May the flock be with you — Quoth Oprah Hen-Free: "Evermore".

Pat Foreman

======================================

References

1. U.S. Poultry & Egg Association website. http://www.uspoultry.org/economic_data/

2. American Egg Board website:

http://www.aeb.org/egg-industry/industry-facts/egg-production-and-consumption

http://www.aeb.org/egg-industry/industry-facts/egg-industry-facts-sheet

The rate of lay rate of lay per day on May 1, 2012 averaged 73.6 eggs per 100 layers. Extrapolating this out to a year – (73.6 eggs/100 hens)(365 days per year) = 266.45 eggs/hen/year.